Whether you believe it to be an enduring ethos of our country or a tenet fallen by the wayside, it’s hard to argue against the historical power of the American Dream.

For my ancestors, the Dream drove their decisions, justified their risks, and tempered their struggles. I’ve been blessed with several long-living relatives who, well into their nineties, held on to vivid memories of how the Dream shaped their world. A fascinating commonality was how decidedly uninteresting they perceived their lives to be, and how reluctant they were to speak about hardship. I never understood this. To live through the Depression, to come into adulthood during a war, to see such complex social change burgeoning before your eyes… these were all extraordinary circumstances worth recalling!

Or so I thought.

But circumstance, it turns out, is the crux of the problem. Stay with me on this…

It was 2012 when I sat down with my great-aunt Janet (aka ‘Auntie’) to record some family history. Janet lived her entire life with her parents and had become something of a matronly spokesperson. We sat in the small, spotless dining room, my laptop open between us, Auntie sipping her Red Rose tea. Her brother, my 95-year-old Uncle Al, sat nearby, listening and not making eye contact with anyone. I directed my questions at my aunt.

‘Tell me about your parents,’ I began. ‘How did they come to this country?’

Their father, Gustav Werner, was born in 1891, in Westphalia, Germany. He was working in the coal mines in his late teens, and war was breaking out in Europe. He did what any life-loving, wanderlusting, uncommitted young man would do: He hightailed it out of the country to dodge the draft. To be exact, he took a job on a tramp ship.

The tramp made its way west, eventually docking in Bayonne, NJ. There, at age eighteen, Gustav illegally jumped ship into a foreign country where he knew no one, owned only the clothes on his back, and spoke just a few words of English.

This fact alone stunned me. Could I have done something so bold, so terrifying, at eighteen? And I wondered, what motivated him more? Fear of war? Opportunity in the United States? Or both, in equal measure?

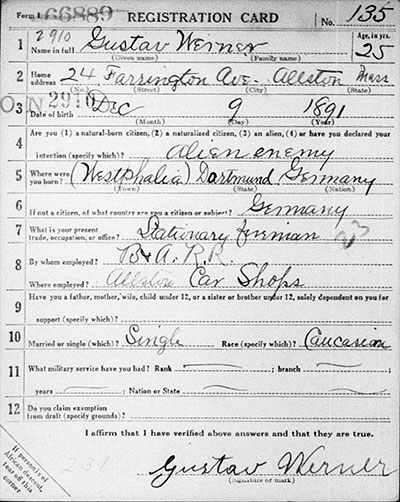

Gustav accepted whatever work he could find on the ships in port: Deck hand, coal shoveler, cargo loader. At night he read the newspaper cover to cover, learning English and plotting his next move. A second tramp ship ferried him to Boston, where he jumped again and took a job as a stationary fireman at the railroad. A Finnish girl stole his heart, and they were soon married. A baby named Albert followed shortly. But before long, war came calling again, and Gustav registered for the United States draft.

Are you (1) a natural-born citizen, (2) a naturalized citizen, (3) an alien, (4) or have you declared your intention (specify which):_______________________

Gustav wrote alien enemy.

The United States was, after all, at war with Germany. And he was an undocumented immigrant.

The United States was, after all, at war with Germany. And he was an undocumented immigrant.

I’m not certain whether his alien enemy status prevented him from being drafted or not, but he was never called up. By 1918, Spanish Flu was rampant and Gustav lost his wife and a second baby to illness. He was now single, with three-year-old Albert to provide and care for.

Meanwhile, in Holland, Kathrine Keisper was facing a difficult choice. Her family was immigrating to America, and she wasn’t sure she wanted to accompany them. She was eighteen, quite possibly in love, and had a good job as a maid for a wealthy woman. She decided at the last moment she would not leave Holland. But when her whole family departed, she knew she’d made a terrible mistake. By then, the money intended for her passage had been spent. Katherine’s employer took pity on her and offered to lend her the money for a steerage ticket to the US. When Gustav met Katherine, she was working as a laundress to repay her loan. They met at a dance club; their native languages were similar enough to facilitate courting, Auntie told me, and they both enjoyed the pickled herring served as refreshments at the club. When they married, Katherine adopted young Al as her own. She went on to give birth to four more children.

At this juncture, I steered the conversation toward life during the Depression. I was working on a manuscript, and I was eager for firsthand anecdotes of the family’s struggles. I immediately sensed discomfort in the room, but I pressed for details anyway. Again, I thought, to have lived through such a thing is astonishing, certainly nothing to be ashamed of. Silently, I also thought, you people cannot die before I write this down! Auntie obliged my curiosity and told me enough stories to fill a separate blog post (stay tuned for that). She closed the topic by saying firmly, ‘There was never a shortage of love.’

Then, with a long glance at Al, she said, ‘For 25 years, we all believed Katherine was Al’s birthmother. It wasn’t until he joined the Navy during WWII and our parents had to produce his birth certificate that we learned he was a half-sibling.’

I gaped at her. ‘How is that possible?’ I whispered in dismay.

‘You simply didn’t ask questions back then,’ Auntie said. ‘And it didn’t matter anyway. He was always our brother.’

The conversation turned to WWII, which at the time I wasn’t particularly interested in, but I took notes anyway, thank goodness. Auntie explained how Al joined the Navy as a Seabee, or C.B., the Navy’s Construction Battalion. The Seabees were skilled workers trained to build in war zones — which meant dropping their tools to take up their weapons at the first sign of conflict. Al was a carpenter’s mate, sent to Okinawa to build bases after the invasion. Auntie glanced at Al again. ‘Isn’t that right, Al?’ she prodded.

He nodded slowly. I was about to ask Auntie another question, but Al spoke quietly from his chair. ‘The Seabees wore green uniforms. The regular crew wore blue. I stole a blue uniform on the way to Okinawa, to wear when I wasn’t on duty. That way I got better food and bigger servings. And a fresh water shower.’

I shifted to face my uncle. ‘Were you stationed in Japan for the whole war?’ I asked carefully. I expected Auntie to answer for him, but she didn’t. She watched him, waiting.

He stared straight ahead, memories gathering in his mind.

‘I was at the invasion of Sicily, on a destroyer in the harbor. The sky exploded all night long, and they made us stay below. In the morning, the deck was covered in shrapnel. After a few nights of that, I couldn’t take it any more. I couldn’t spend another night down there while the sky was on fire. So I made a choice. I took my chances and slept on the deck. In the middle of the night, there was a huge explosion. I was sure we’d been hit. But it was just the ship blowing out its stacks. I woke up covered in black soot and happy to be alive.’

Al kept talking, recalling stories from the war with incredible clarity. He talked about coming home, marrying a lovely wife, having a successful career. He had an insatiable interest in new technology. He loved to dance and to travel. He did not believe in self pity.

It took me years, and the entirety of constructing this blog post, to understand why Al wouldn’t talk about the Depression. My uncle didn’t want to talk about his life’s circumstances. He didn’t care to recall the hardships or the disappointments of his life. What he wanted to talk about were the choices he made and the experiences he had because of them. Seventy years after that night on the ship in Sicily, the night he chose to sleep on the deck, he could still see the exploding sky, smell the soot from the stack, hear the battle ranging in the distance. His life was rich and full, not because of his circumstances, but because of his choices.

All of which were his American Dreams.